Sensing Tastes and Odours

Objectives

- To learn about the way insects sense their environment through taste and smell

Topic Outline

- Part 1: Introduction, minilecture on olfaction and gustation

- Part 2: Olfaction and gustation

- Part 3: Nerve cells

- Part 4: Humidity receptors

- Part 5: Distribution of sensilla

- Part 6: Function

Activities

- Minilecture: Olfaction and Gustation

- Part 2: Feeding video

Part 1: Introduction

A European honey bee visiting a native passionfruit flower in north Queensland [Image: B.W. Cribb]

Introduction

In this module, we explore the way in which insects sense the chemistry of the world. To find food insects need to be able to discriminate food from non-food and toxins from nutrients. Many must be able to find water. Insects also need to be able to find and recognise mates. This information is accessible through chemoreception.

Small molecular weight compounds are volatile and can be sensed at a distance through air. Smell is sensed through structures on the antennae and on some regions associated with the mouthparts such as the palps.This process is called olfaction and it is the initial phase in food and mate-finding.

Solid or liquid chemicals are tasted by direct contact. Many of these chemicals are large molecules than do not travel through the air well. This process of direct tasting is called gustation, or contact chemoreception. Taste occurs in the region of the mouth parts but it can also occur through sense organs on the tarsi and the ovipositor. Gustation is frequently the second phase in locating food and mates, brought into play after olfaction brings the insect into the appropriate area.

Chemosensory organs used by insects to taste and smell must allow the chemicals to penetrate the exoskeleton. We see the solution in a range of tiny hair-like and plate-like structures that house the endings of the sensory neurons. In this module you will learn about their structure and function (see also textbook: Chapman chapter 24).

The cells associated with the cuticle can also be modified for sensing and secreting. Insect sense organs are diverse, able to detect many different stimuli and encoding sensory information into nerve impulses travelling to the central nervous system.

|

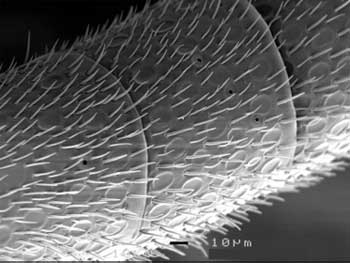

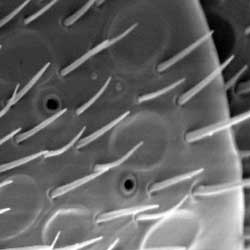

The Sensillum

Insects smell and taste through cuticular projections called hairs or setae. These have pores in the surface through which the chemicals enter but the pores are so small (in the nanometer range for many) that they are only seen at very high magnifications. The correct term for these cuticular structures is sensilla (plural) or sensillum (singular). Table 1 presents some of the different terminology. See if you can recognize some of these sensilla in the photographs.

|

|

The antenna of a bee shows a range of sensilla used in olfaction. The black holes contain small sensory pegs. Note the plate-like discs. Image was taken using a scanning electron microscope. [Image B.W. Cribb]

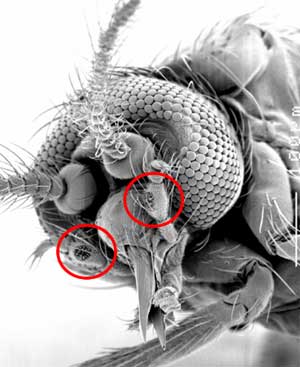

| Head of a coastal biting midge, Culicoides sp. Image taken with a scanning electron microscope. Palps are circled [Image: B.W. Cribb]

|

Morphological description of sensilla is important since overall shape and length correlate with internal function. The presence or absence of grooves is important. Length and tip shape are also often recorded. Tip shape can be sharp or blunt. As an example, in the mosquito, Culex quinquefasciatus, 17 functional classes of sensilla trichodea are identified as 3 short sharp-tipped, 9 short blunt-tipped type I, and 5 short blunt-tipped type II sensilla (see Hill, S.R., Hansson, Bill, S., Ignell, R. (2009) Characterization of antennal trichoid sensilla from female southern house mosquito, Culex quinquefasciatus Say. Chemical Senses 34, 231–252.). |

|

References

Cribb, B.W. (1997) Antennal sensilla of the female biting midge: Forcipomyia (Lasiohelea) townsvillensis (Taylor) (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae). International Journal of Insect Morphology and Embryology, 24, 405-425.

Shanbhag S.R., Müller, B. & Steinbrecht R.A. (1999) Atlas of olfactory organs of Drosophila melanogaster 1. Types, external organization, innervation and distribution of olfactory sensilla. International Journal of Insect Morphology and Embryology, 28, 377-397.

Mini-lecture:

Mini-lecture: